Dial-A-Song

- This article is about the Dial-A-Song phone service.

For the 2015 and 2018 iterations, see Dial-A-Song (2015) and Dial-A-Song (2018).

For the interactive website, see DialASong.com.

For the 2002 compilation CD, see Dial-A-Song: 20 Years Of They Might Be Giants.

Dial-A-Song is a telephone service operated by They Might Be Giants that originally ran from 1983 to 2006. It returned in 2014, and has run continuously since. The service is currently active and can be reached at (844) 387-6962.

The service was originally available as "a regular phone call to Brooklyn," at the number (718) 387-6962. Dial-A-Song consisted of an answering machine in John Flansburgh's apartment, which would pick up calls and play back a song in the place of an outgoing message. The model of answering machine employed changed throughout Dial-A-Song's tenure, but most machines played back the message via a cassette tape. This system made it easy for the band to record demos, jingles, or previews of studio tracks onto cassettes and then queue them into the machine. Dial-A-Song was typically updated daily, and most tracks stayed in rotation for a while after their initial appearances.

In both 2015 and 2018, the band restarted Dial-A-Song, focusing on distributing new music on a weekly basis for one year each. New songs were made available through various online mediums including DialASong.com and a toll-free phone number that has been running since late 2014, (844) 387-6962.[1] It currently plays from a selection of songs from the 2015/2018 Dial-A-Song projects. In 2013 the band launched the They Might Be Giants App. It works as a modern update of the Dial-A-Song concept, and features a new song every day.

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

Early years[edit]

Dial-A-Song began in November 1983, when the band was forced to take an unexpected break from live performances after a few unfortunate setbacks.[2][3] John Flansburgh had moved into a new apartment in Bed-Stuy, and was thoroughly burglarized the day that he moved in. All of his belongings, including his stage equipment, were stolen. Flansburgh: "I moved into this apartment for one day, and unfortunately some of the other occupants in the building were drug dealers, and they weren't too happy about me being in the place. So when I went off to work they set me up to be robbed, I basically lost all my worldly positions." In the same week John Linnell, working as a bike messenger, broke his right wrist in a bicycle accident. Linnell: "I didn't maintain my bike very well — that was the thing that brought me down. I've never been clear on how this happened, but somehow the bike froze and I went over the handlebars with about forty pounds of stuff on my back and landed on my right hand. That ground the band to a halt for about four months while my wrist was healing."[4]

The band had been playing regularly in New York, and didn't want to lose their momentum. Flansburgh, in a 1989 interview: "We knew we weren't going to be able to perform live for a few months at least, and we had all these songs that we really wanted to get out to the public. So, in order to hold on to those 35 people who were truly interested in what we were doing, we figured we would start the Dial-A-Song service."

Flansburgh had the idea for Dial-A-Song a few years prior to launching it. The concept was based on Dial-A-Prayer, a Christian phone service that played back inspirational messages through an answering machine.[5] Flansburgh had called Dial-A-Prayer as a child, and when consumer answering machines started to become available, he thought the medium would be an effective way to independently release songs. Flansburgh first wanted to start the service in the early '80s, when he and Linnell shared an apartment. Linnell opposed the idea. "I tried to talk him out of it because we just had the one phone. Anyone who tried to reach us would have to listen to a two-minute song first."[6] In late 1983 Flansburgh moved in to apartment by himself. "Pretty much as soon as I got my own apartment, we started doing the Dial-A-Song thing because we were free to do it. We didn't have to share the phone line with a roommate."[7] Around this time, Flansburgh bought the first machine for Dial-A-Song at a Crazy Eddie store[8], and housed it inside a suitcase in the kitchen of the apartment.[9] Originally, the phone number was on Flansburgh's home phone line, as he could not yet afford a second. An article from a February 1990 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer reads: "It was almost impossible for Linnell to get a hold of his partner, whose phone was quickly clogged by about a hundred calls a day."

The band initially recorded "20-30 songs" for the Dial-A-Song project[10] with equipment that had previously been used for the band's early demos and home recordings. Equipment used during the first year of Dial-A-Song included the TEAC 4-track tape recorder, Linnell's Farfisa Combo Compact organ and Micromoog synthesizer, a drum kit, Flansburgh's guitar and the BOSS DR-110 Dr. Rhythm[11], the band's first drum machine[12]. "Toddler Hiway" was the very first song played on Dial-A-Song, according to Linnell in a 1998 interview on This American Life:

John [Flansburgh] said 'I've set [Dial-A-Song] up.' I was living in a different part of Brooklyn, so I phoned him up, and it was 'Toddler Hiway.' And he recorded it really quietly, because we had this problem with the phone machine where a loud sound, with this particular model, would actually tell the machine that that was the end of the message.

Some of the first songs written for Dial-A-Song in 1983 were "How Much Cake Can You Eat?", "Swing Is A Word (Six Feet Down)" and a cover of Tommy Dorsey's "I'm Gettin' Sentimental Over You", which would often be replayed on Dial-A-Song in the late-1980s as a "Dial-A-Song triple play"[13]. Several songs recorded by the band before the creation of Dial-A-Song were also entered into rotation. These included "Cowtown", "Now That I Have Everything", "Heptone", "Youth Culture Killed My Dog", "Alienation's For The Rich", "Weep Day", "Hell Hotel", "I Wouldn't Be Mad", "I Need Some Lovin'", "Penguine" and "Cabbagetown".[14] Flansburgh on recordings made for the Dial-A-Song service[15]:

There were unique recordings made just for the service (often streamlined arrangements with the vocals kind of jacked up for extra clarity) and those were very simply tracked–sometimes directly on to the outgoing cassette, often rerecorded as tapes wore out (or the desire to use the coveted "leaderless" cassette to facilitate more immediate engagement from listeners) and all of this activity was not in any way archived.

The service was initially called "Dial-A-Machine." Early promotional material indicates that the name likely changed to Dial-A-Song between June and July 1984. Flansburgh: "Originally it was called Dial-A-Machine because it seemed like a funny idea."[16] There is currently no evidence to suggest that the service had a name before mid-1984. Early advertisements for the service simply print the phone number without a title, and the earliest known appearance of the Dial-A-Machine title is a May 1984 show poster. For nearly a year after its creation, the number was at the 212 area code, as the 718 area code covering Brooklyn and other boroughs was not created until September 1984.[17] John Flansburgh, in a 2015 interview: "When they invented the 718 area code, I was afraid that Dial-A-Song would be kind of ruined, because we would be exposed as kind of non-New York City residents. There was such an expansion-team feeling about the 718 area code."

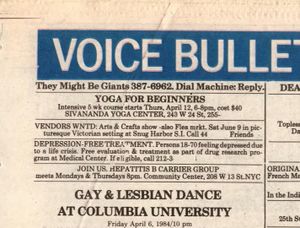

Dial-A-Song attracted a different kind of audience to that which would attend the bands shows, which were typically late-night gigs at performance art spaces. The band advertised Dial-A-Song in the "Voice Bulletin Board" classified section on the back of The Village Voice, a New York-based alternative newsweekly. Flansburgh would place these advertisements as personal listings, as it was cheaper than placing a commercial advertisement. The band was afraid to advertise anything about themselves on Dial-A-Song as a result. Early outgoing messages would have no information about the band or their upcoming shows, it would only play the song and automatically hang up. The earliest known advertisements for Dial-A-Song in The Village Voice date to March 1984.[18] Once the band started releasing music commercially, they advertised the number on the back covers and liner notes of their releases. The 1985 Demo Tape and Wiggle Diskette both carry the number, in addition to many earlier demo tapes, which had the number written on the cassette labels. Once a recording was released commercially, it would be removed from the Dial-A-Song rotation. After an album was released, all associated songs (and the demos of those songs) would be culled, and generally only unreleased material would remain.

In the early years of the service, it was intended that people would leave feedback on the songs. Anybody could leave a message on the Dial-A-Song machine after the song had finished. The band has released a few of these messages. The track "Untitled" is a recording of a confused woman and her friend on a conference call, who were unknowingly being recorded. The spoken vocal in "I'm Def" is taken from a Dial-A-Song caller, and the backwards speech at the start of "I'll Sink Manhattan" is an appreciative message from the New York Police Department. The band had stopped taking messages in 1987 or early 1988.[19] Flansburgh: "It got to be too much, just listening to a half-hour of messages every day."[20]

John Flansburgh reflected in a 2015 interview:

The one thing that I'll be forever grateful for is that the original Dial-A-Song just introduced the band to so many people in such a singular way. As much as bands try to sort of set themselves apart from the crowd, it's very difficult to give people a different experience. A lot of the ways people are introduced to bands are very standardized, and the great thing about the Dial-A-Song thing was that it was so different. It really put the songs first. It really just changed us. It really focused us on what we could do that was our own unique 'us.'

Later history[edit]

As the band gained a following and secured a record deal with Bar/None, they continued to share music through Dial-A-Song. It was often considered to be a somewhat intimate experience, as the answering machine could only take one caller at a time. Some tracks were demos of songs that would go on to appear on studio albums. Other tracks were exclusive to Dial-A-Song, and have not appeared outside the service. In the mid-1990s, fans collected recordings of known Dial-A-Song tracks into bootlegs. Two of these bootlegs, Power Of Dial-A-Song and Power Of Dial-A-Song II, are still well known among fans, despite their relatively low fidelity (having been recorded from a cassette broadcast over a telephone line). In 1992, John Linnell discussed the service's low-maintenance nature in an interview with Arthur Durkee:

Dial-A-Song will never die. In fact, I'm sure long after we've broken up, stopped making records, done all that stuff, that we could still do Dial-A-Song. It's so easy. It's just a phone machine. Doesn't require any work. I guess the work is doing the demo for the songs that we'd be making anyway. They don't have to sound okay, they just have to be audible: 'cause they don't sound okay once they go over the phone line anyway.

Many TMBG releases—up to the early 2000s—bear some mention of Dial-A-Song, often with little information besides the service's name and an occasional slogan or phrase. For international releases, the number included the country code for America, 0101 or 01. The band also occasionally referenced the phone line elsewhere, such as in the name of the compilation album, Dial-A-Song: 20 Years Of They Might Be Giants. Flansburgh is shown recording an early demo of "I Can't Hide From My Mind" in Gigantic.

To supplement Dial-A-Song, the band began dialasong.com, a Flash site that let visitors listen to various TMBG demos and other songs.

Decline and disconnection[edit]

In the mid-2000s, due to technical failures, the band started having difficulty maintaining Dial-A-Song. The primitive answering machines used were generally unreliable, and had to be replaced frequently. Despite the band's acquisition of a new vintage machine in April 2006, the stress placed upon the answering machine in addition to its age caused excessive wear, and the machine broke down soon after. The final song that appeared on Dial-A-Song was a demo of "We Live In A Dump". On November 15, 2008, the Dial-A-Song number was officially disconnected.

Because the band had started taking advantage of the Internet to share demos and one-off tracks, they grew less invested in sustaining Dial-A-Song. In addition to dialasong.com, Free Tunes and the They Might Be Giants Podcast achieved essentially the same goals as Dial-A-Song, both featuring new songs and other rarities for fans to hear. In January 2013, the band also introduced a mobile app, which was expected to take over where Dial-A-Song and the podcast had left off. However, the app has not featured any new material, and instead behaves more similarly to the TMBG Clock Radio.

Some fans of the band have attempted to continue the "spirit" of Dial-A-Song by purchasing the number and releasing their own demos through the phone line. However, these attempts have generally been unsuccessful and short-lived. A This Might Be A Wiki admin made an attempt to briefly imitate Dial-A-Song through Dial-A-Wiki, which used an original number and Google Voice to play old TMBG demos, but this ran for only a brief period in 2010.

Revival[edit]

In October 2014, They Might Be Giants posted a teaser video for the triumphant return of the Dial-A-Song website in January 2015. The description of the video reads, "For 2015 They Might Be Giants will be posting a new song online every week at dialasong.com. Yep. Exactly." In December 2014 the Dial-A-Song phone line returned with the toll free number (844) 387-6962.

The new incarnation of Dial-A-Song released one new song a week throughout the year. The songs were distributed via through both the new toll-free phone line and online streaming on the band's ParticleMen YouTube channel, where each song had an accompanying video. MP3 or WAV files of the songs were also emailed to subscribers of a service known as Dial-A-Song Direct. Most of the songs from the 2015 service were compiled onto three albums: Glean, Why?, and Phone Power.

In September 2017, the band announced that Dial-A-Song would return in 2018 with "brand new songs on the first and third weeks of the month for the first half of the year, with tracks from the brand new album getting the spot light on the second and [fourth]...Either bi-weekly or weekly if we can handle it."[21][22] Though this pattern was not strictly followed, there was generally a new video each week except for the month of August. Songs not on I Like Fun from 2018's iteration were compiled into the albums The Escape Team and My Murdered Remains.

Answering machines[edit]

Due to the temperamental nature of tape-based answering machines, the band went through a few different makes and models throughout Dial-A-Song's lifetime. From 1983 to 1993 the band used cassette answering machines. In 1993 they switched it to an automatic computer voice mail system. The computer was worse quality and unreliable, so the band alternated between a computer system and the cassette machine over the next few years.

In the summer of 2002, both the Dial-A-Song answering machine and its backup apparently melted in Flansburgh's apartment. Fans responded by sending new models to the band, and in April 2003, Dial-A-Song returned via a Record-A-Call 675, which the band purchased after a fan found it on eBay. TechTV provided TMBG with a new computer system for Dial-A-Song in the following year, but technical difficulties brought the system to an end by 2005. In 2006, the band reported their acquisition of a Record-A-Call 690 in a newsletter in April.

Slogans[edit]

Throughout its history, Dial-A-Song has had various slogans attached to it. These include:

- 25 hours a day, 6 days a week

- Free when you call from work

- Always busy, often broken

- Diet music at the end of the tunnel for a new generation

These had some variations, including "Still free, often busy", and the more honest "24 hours a day". Listings of the number on releases sometimes also included gentle encouragements, such as "Don't be afraid" and "Dial-A-Song awaits you"—"At no extra charge".

Some new phrases were introduced for the 2015 revival:

- It's for you

- Our options have changed

- Ring Ring Ring

- My Big Teeth Gnash It†

- High Time Ants Get By†

- Seth, I'm in Thy Bat Egg†

† These are anagrams of They Might Be Giants (some by John Linnell), from the old tmbg.com

Songs on Dial-A-Song[edit]

Over 100 songs and other recordings are known to have been featured on Dial-A-Song during its original 23-year run from 1983 to 2006. These included demos or early sketches of songs that would be featured on albums, one-off tunes, "theme songs" for Dial-A-Song itself, and messages to the caller, among other things. The band has indicated that all of the tracks on their early albums were "filtered" through Dial-A-Song at some point. Because the band often shared unfinished or half-imaged material through Dial-A-Song, it is possible to observe how some songs, such as "Rat Patrol", evolved before they were released—the demo of that song, which was sung by Flansburgh and not Linnell, has a vastly different melody than the album version.

The 2015 and 2018 revivals of Dial-A-Song have featured large amounts of new material from the band, including a new song every week for a total of 52 songs in 2015, and dozens of additional new ones in 2018.

Gallery[edit]

Promotional material[edit]

Advertisements in The Village Voice[edit]

Other advertisements[edit]

Trivia/Info[edit]

- In an interview with The Daily Collegian on October 27th, 1987, it was stated that the band wrote "six or seven new songs to the rotation every month."

- In a New York Magazine article from February 2nd, 1989, it was also stated that Dial-A-Song was an "underground hit" and the service got "more than 100 calls a day."

- In an interview with Imprint from November 2nd, 1990, Linnell was asked about how often they changed the songs on Dial-A-Song: "Um well, they're supposed to be changed every day, John [Flansburgh]'s landlady is supposed to change the set, which really isn't a big deal; and I don't know if she does it every day anyway. I think it's like permissible to miss a day. But it's a really easy thing to do."

- John Flansburgh on the success of Dial-A-Song from BMI magazine, April 21st, 2005:

The success of the original Dial-A-Song project really informed us about the upside of pushing things a step further than the standard approaches of how to present a band, and was kind of a preview of the “gift economy” idea people talk about now. I kind of recoil from the “everyone said we were wrong!” show business tales, but it is notable to me that among most of the smart gatekeepers in the record business we encountered it seemed like Dial-A-Song scanned as a small-time, slightly desperate move. Whatever the notoriety and name recognition Dial-A-Song brought us, record company folks seemed more concerned about what the project undid—the ability to control the release of a song into the world, the ability to contour the band’s story to the press, radio, etc. Selling mystery was the first step in selling rock music and songs on a phone machine sounded dumpy and un-mysterious to them. Of course we had a different perspective at the time, and we also had some different inside knowledge. I think about how the demos of Don’t Let’s Start or Birdhouse in Your Soul played on Dial-A-Song regularly for a year before those recordings came out, and it didn’t really undermine anyone’s promo work. In fact it seems no one even knew or noticed.

- Early into the Dial-A-Song service, a friend of Flansburgh left a message impersonating Robert Christgau of the Village Voice. Flansburgh mentioned this in a 2018 interview:

The one that always sticks out in my mind is when a friend we had lived within Park Slope called up and did this very, very effective impression of Robert Christgau, something like: “Hello, They Might Be Giants. This is Robert Christgau of The Village Voice, and I just want to say that your band stinks, and I’m going to do everything in my power…” And it was extremely deadpan and very, very cold. The first time I listened to it I was pretty positive it was real, and I thought, “Wow, how much evil is there in the world that a rock critic would take time out of his day to call you up, tell you he hated you, and promise to destroy your career.”

- In the same interview, Flansburgh mentioned that a woman took down the seven-digit number to blow off unwanted suitors, causing the band to get messages for her.

- One of the early promotional tools for Dial-A-Song was a four-sided spinner with a stamp on it. The earliest known appearance of the spinner was in a September 1985 article from Oh No! Noho!

External links[edit]

- DialASong.com (archived) - Homepage for Dial-A-Song and Dial-A-Song Direct

- Documentary by Mike Buffington on the machines used for Dial-A-Song